Facebook’s Name-Change Changes Nothing But Its Name

Photograph by Annie Spratt

In the acclaimed advertising series Mad Men, struggling dog food company Caldecott Farms comes to Sterling Cooper hoping to solve a PR problem. Word has gotten out that Caldecott uses horse meat in their dog food. Customers are understandably upset and repulsed.

Caldecott lays a challenge at the feet of Sterling Cooper’s ad agency, to do whatever they must to turn public opinion around, but with two caveats: they cannot change the product, and they cannot change the name.

To which Sterling Cooper’s Creative Director (the infamous Uber-innovative) Don Draper makes clear that the task is near impossible.

Of course, he’s right. Being presented with the devil’s bargain of “sell our crappy product without making it less crap” is a temptation to many marketers. But even the best creative is thwarted by leaders who don’t wish to face the truth about themselves.

Nothing solves for dog food that is really horse meat once the cat (errr, horse) is out of the bag.

What’s In A Name?

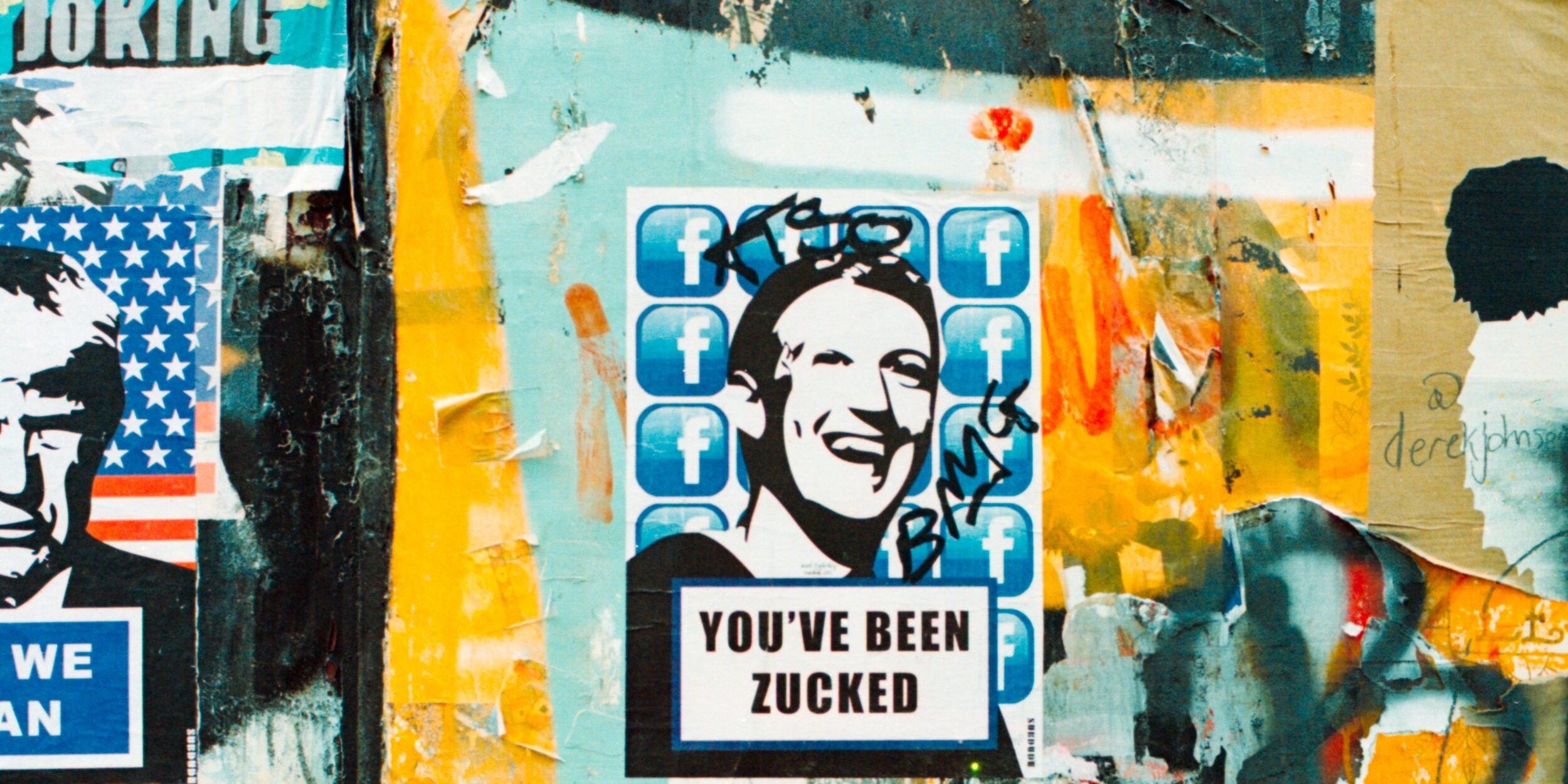

In the “truth is stranger than fiction category,” Facebook announced last week that it would be changing the name of its parent company. Renames are a sticky decision, and a successful one has a lot to do with timing. The worst possible timing?

Probably in the middle of a tidal wave of bad press.

The new name, Meta, will encapsulate the company’s suite of VR and AR solutions proudly dubbed “the Metaverse.”

Putting down the truckloads of cultural commentary for a moment, and picking up the brand commentary, it would appear that Facebook (like horse-meat peddling Caldecott Farms) doesn’t really get what’s wrong here. They’re acting as if the last month (nay 6 years) of brand destroying, whistleblowing, company-wide revelations about negligence, dishonesty, and ethically wrong-wrong-wrong actions HASN’T been all over the public’s news feeds. Except it has.

We all know there’s horse meat in our dog food.

But instead of acknowledging it and vowing to create corporate (and true cultural) change, Facebook is hoping a little new-name misdirection will relieve the pressure to actually atone. The consumer’s voice is growing louder and clearer. Calls for transparency and change are rampant.

But from Facebook’s standpoint, dissecting a prestigious past (especially when some shady secrets might be buried there) doesn’t exactly sound like fun. You know what does?

The metaverse.

A Whole New Thing

The late Anthony Bourdain would often talk about how he wouldn’t eat seafood served for Sunday brunch because he knew it was what the chef was unable to sell Friday and Saturday night for dinner.

Look! It’s not old fish. It’s a whole new thing!

And that’s what Facebook, from a brand standpoint, is hoping their investors and the public will believe about their name change. That their brand, tasting of horse meat and smelling like old fish, is really a whole new thing.

Which it isn’t.

Photograph by Thought Catalogue

To regain control of their tarnished narrative, Facebook is shifting the conversation to something else – anything else, it seems. The metaverse, their new name, Apple making things hard on small businesses, retooling reels, and using young people as their “north star.” None of these are pointing out a solution as much as drawing the camera away from their mess.

-

Brands have been doing this sort of thing for a long time.

-

Dell pretending their laptop batteries didn’t catch fire – then issuing a recall.

-

Apple pretending the iPhone 4 didn’t drop calls more than usual – which it did.

-

VW rigging their diesel-powered cars to lie on emissions tests.

-

Sony hiding rootkits in their music CDs which were then installed on customer’s PCs.

In all these cases, the ones who suffered most weren’t investors or even the brands themselves, it was the consumers. Consumers who were met with the knowing neglect of brands they trusted and were left unprotected because of that neglect.

Facebook, and its platforms, have knowingly manipulated, neglected, and hurt the very people who use them, and they did it to keep making money and fame for themselves. That is all blatantly true and clear.

With their name change, they are set to keep doing it, in full view of everyone, into the future. This is the worst kind of behavior, from the worst kind of brand – one that, truly deep down, doesn’t care about its customers but claims it does.

More Than A Name

Eric Dezenhall, whose professional life is dedicated to helping companies and clients weather controversy, writes in his brilliant book Glass Jaw that many brands have the,

“…tendency to address reputational crises as if they are ‘communications problems’ versus something larger and more structural.”

If Facebook’s woes could have been erased with a new name and branding, that would have worked in 2019 when they introduced their blue “F app” and rebranded the parent company as FACEBOOK.

It didn’t work then because, as Dezenhall explains, the brand’s issues are more than just skin or name-deep. They are structural, going all the way down to the foundation. And though Halloween is nearly upon us, putting on another costume doesn’t change the monster within.

For brands everywhere, that should be the biggest takeaway from Facebook’s extended run in the gutter. An issue with the way the brand treats customers or makes its products is not a problem of perception – it’s a problem with the brand itself.

Our encouragement to brand owners, those in the field of technology especially, is to find the truth in all those lines of code. Truth that comes from conviction, from the world-changing impact of what you build, from looking yourself in the mirror when the intention of a thing has been lost.

The brand must have a strategy and a system for holding the whole organization accountable to its highest and best use. When the brand becomes a tool for distraction, you are on a slippery slope that few recover from.

Regardless of how exciting Meta’s metaverse is, it will taste and smell like Facebook until they do the hard work that every brand must do: being asked hard questions and giving answers that organically grow out of their intentionally refined business practices, brand integrity, and dedication to put the customer first.

There’s still time for us to be “friends,” Meta. But the clock is ticking.